How Archibald Alexander Relates to

the

Heresy of

Decisional Regeneration

![]()

![]()

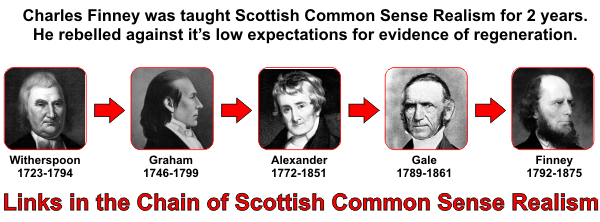

For a biography of Archibald Alexander, click here. The following exerpts are from Archibald Alexander's Thoughts On Religious Experience, written in 1840. Before we read Archibald Alexander's diminished view of the immediate activity of the Holy Spirit, let's start with Charles Spurgeon's description: "All that the believer has must come from Christ, but it comes solely through the channel of the Spirit of grace. Moreover, as all blessings thus flow to you through the Holy Spirit, so also no good thing can come out of you in holy thought, devout worship, or gracious act, apart from the sanctifying operation of the same Spirit. Even if the good seed be sown in you, yet it lies dormant except He worketh in you to will and to do of His own good pleasure. Do you desire to speak for Jesus—how can you unless the Holy Ghost touch your tongue? Do you desire to pray? Alas! what dull work it is unless the Spirit maketh intercession for you! Do you desire to subdue sin? Would you be holy? Would you imitate your Master? Do you desire to rise to superlative heights of spirituality? Are you wanting to be made like the angels of God, full of zeal and ardour for the Master's cause? You cannot without the Spirit—"Without me ye can do nothing." O branch of the vine, thou canst have no fruit without the sap! O child of God, thou hast no life within thee apart from the life which God gives thee through His Spirit! Then let us not grieve Him or provoke Him to anger by our sin. Let us not quench Him in one of His faintest motions in our soul; let us foster every suggestion, and be ready to obey every prompting. If the Holy Spirit be indeed so mighty, let us attempt nothing without Him; let us begin no project, and carry on no enterprise, and conclude no transaction, without imploring His blessing. Let us do Him the due homage of feeling our entire weakness apart from Him, and then depending alone upon Him, having this for our prayer, "Open Thou my heart and my whole being to Thine incoming, and uphold me with Thy free Spirit when I shall have received that Spirit in my inward parts." Archibald Alexander's did not see the Holy Spirit this way. He did not see the significance of regenerated man's dual nature as described in Romans 7 and the necessity of immediate walking in the Holy Spirit as described in Romans 8. His restrictive view of the activity of the Holy Spirit was learned from William Graham and other Scottish Common Sense Realists. He taught students at Princeton Theological Seminary the Holy Spirit was limited to assisting the MORAL PERSUASION of the Word of God. He wrote, “genuine religious experience is nothing but the impression of divine truth on the mind, by the energy of the Holy Spirit”. This view evolved into a purely psychological view of saving faith by the end of the nineteenth century. Long before it decended into what was in effect, a "bare faith", non-election theology, it questioned whether there was any discernable evidence of supernatural regeneration. It was the lack of expectations of a supernatural change of character in regeneration that Charles Finney rebelled against. The immediate activity, or "religious affections"of the Holy Spirit is central to the understanding of evangelical salvation. The fight between Old and New Side Calvinists at the First Great Awakening was not a new fight. Before the First Great Awakening, many influencial Old Sides had abandoning the supernatural views of the Bible and adopting purely metaphysical explanations for the activity of the Holy Spirit that fit the Enlightenment view of "reasonable" Christianity. After the First Great Awakening, the New Lights started their own churches, so it was quite common to have a Presbyterian New and Old Side chuches in the same community. When Alexander was a teenager, a man told him if he were born again, "you would know something about it!" Alexander wrote, "It led me to think more seriously whether there were any change. It seemed to be in the Bible; but I thought there must be some method of explaining it away; for among the Presbyterians I had never heard of any one who had experienced the new birth, nor could I recollect. ever to have heard it mentioned." If you read his biography, you'll find he did have significant religious affections when he was 17, which he later dismissed as meaningless when he was tempted, and gave into sin. He did not understand the dual nature of regenerate man described in Romans 7 and the need of walking in the Holy Spirit described in Romans 8, and when he adopted William Graham's view of regeneration, Alexander said of his religious affections, "such experiences are not uncommon, and are often taken for conversion". The ironic thing is his momentary sin filled him with "unutterable anguish", so whether he was in the throws of law works, or regenerate, is quite irrelevant to the fact that his religious affections were of the Holy Spirit. In 1812, Hopkinisians and Bellamites were the premier New Light Calvinists ministers in America. But that year, Archibald Alexander established a Theological Seminary that would change the face of American New Light Calvinism. by 1840, the disciples of Princeton’s Scottish Common Sense Realism had replaced the Bellamites and the Hopkinsians as the most influencial New Light Calvinist ministers. This glowing report was reported in an issue of Lyman Beecher’s (a Hopkinsian) Spirit Of The Pilgrims in 1828: “It is well known that the chair of Moral Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh has been almost the throne of Metaphysics, for England and America. The successive monarchs of the dynasty have each endeavored to erect his empire, in some degree, at least, upon the ruins of his predecessor's, and each has generally bestowed as much of his attention upon the little which he wished to demolish, as upon the far greater portion which he was ready to confirm. Men frequently dwell with more interest upon the few points on which they differ, than upon the many in which they agree; and the metaphysical philosophers have brought out a few spots of debatable ground, into a far more conspicuous rank than they deserve, when compared with the extensive regions of which they have settled and harmonious possession, and which are of undoubted beauty and fruitfulness. These regions, the work of which we are speaking designs to occupy; and they are, almost entirely, regions of unquestioned truth.” Finney incorrectly identified this abandonment of the moment of regeneration as identifiable as “orthodoxy”, thinking that Scottish Common Sense Realism was what Old School Pilgrims taught. Finney was wrong. Scottish Common Sense Realism came to America with John Witherspoon in 1768. Alexander starts of with a simile of the means of salvation (which is in itself a statement of evidence of the predetermined will of God). The “cause and effect” reference is the way New Light Calvinism moved away from the “religious affections” understanding of Jonathan Edwards. The Holy Spirit will not be mentioned for many pages, and only then as an agent that quickens scripture. Readers need to learn about predetermination and the consecutional basis of New Light Calvinist saving faith before going any further, or you will not understand Alexander. He is on Orthodox ground because all the means of regeneration, the cause and effect, are predetermined by God. But the metaphysical language will seem like “bare faith” to future generations of Princeton graduates after the Civil War who “conveniently forgot” that predetermination is the consecutional basis of saving faith. This is a Scottish Common Sense Realism false analogy for regeneration that replaces the Biblical explanation of regeneration as a supernatural change of character. The seal is the unchanging Word of God. The wax is the mind of man. The analogy is false. Why? Because a mind does nor remain fixed as wax. A mind is not unchanging as a wax impression. Thus starts Archibald Alexander’s reaffirmation of William Graham and John Witherspoon’s position that evidence of religious affections are nearly worthless in determining one’s spiritual state, and the elevation of understanding the Word of God correctly as receiving the truth of the Word of God – this is the beginning of the evolution to fifth generation New Light Calvinist belief that moral persuasion of the Word of God, quickened by the Holy Spirit, is regeneration. There is, moreover, so great a variety in the constitution of human minds, so much diversity in the strength of the natural passions, and so wide a difference in the temperament of Christians, and so many different degrees of piety, that the study of this department of religious truth is exceedingly difficult, In many cases the most experienced and skilful casuist (one who determines cause and effect) will feel himself at a loss; or may utterly mistake, in regard to the true nature of a case submitted to his consideration. The complete knowledge of the deceitful heart of man, is a prerogative of the omniscient God. This is where Jonathan Edwards would start talking about the disposition of the heart, not continue wringing his hands over the impossibility of understanding cause and effect. In judging of religious experience, it is all important to keep steadily in view the system of divine truth, contained in the Holy Scriptures; otherwise, our experience, as is too often the case, will degenerate into enthusiasm. Many ardent professors, seem too readily to take it for granted, that all religious feelings must be good. They therefore take no care to discriminate between the genuine and the spurious, the pure gold and the tinsel…. If genuine religious experience is nothing but the impression of divine truth on the mind, by the energy of the Holy Spirit, " This is the metaphysicalization of regeneration, the path to fifth generation belief of salvation scriptures a saving faith) " then it is evident that a knowledge of the truth is essential to genuine piety; error never can, under any circumstances, produce the effects of truth. This is now generally “now generally acknowledged” is Alexander’s way of saying the same thing Alexander Campbell (Restorationist)and others at the beginning of the nineteenth century were saying – that God had given man the way to understand salvation in a more accurate way than in previous generations (in preparing mankind for His imminent return). This is one of the defining characteristics of a cult…the idea that knowledge hidden until now is available to the initiates who are willing to accept it. The so-called science of phrenology was sweeping through academia at this time- the fantasy that man’s soul could now be understood in the same way man’s physical being. This was religions excuse for throwing off the embarrassing supernatural aspects of salvation in favor of as one writer put it at the time, the “harmonious operation of the moral machinery which the church is employing, and by wHIch she confidently hopes to bring all nations under the sway of Immanuel” “Nothing but the impression of divine truth on the mind” is the metaphysical, man-mechanical replacement of the supernatural God-relational “immediate activity of the Holy Spirit” of Jonathan Edwards. This “means of regeneration” is very close to that of Alexander Campbell (Restorationist Movement). This was Scottish Common Sense realism brought by John Witherspoon to Princeton… “saving faith” as little more than intellectual assent to scripture that has been “energized” by the Holy Spirit. All ignorance of revealed truth, or error respecting it, must be attended with a corresponding effect in the religious exercises of the person. This consideration teaches us the importance of truth, and the duty of increasing daily in the knowledge of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ…If these things be so, then let all Christians use unceasing diligence in acquiring a correct knowledge of the truth as it is in Jesus ; and let them pray without ceasing for the influence of the Holy Spirit, to render the truth effectual in the sanctification of the whole man, soul, body, and spirit. " Sanctify them THROUGH THY TRUTH, THY WORD IS TRUTH," was a prayer offered up by Christ, in behalf of all whom the Father had given him. Notice how the “knowledge of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ” is not completely equated with knowledge derived from scripture. There is still the need to “pray without ceasing for the influence of the Holy Spirit, to render the truth effectual”. If not for this caveat, Alexander would be promoting “bare faith”. Perhaps some one may infer that we believe in a gradual regeneration, and that special grace differs from common, only in degree; but such an inference would be utterly false, for there can be no medium between life and death ; but we do profess to believe and maintain, that there is a gradual preparation, by common grace, for regeneration, which may be going on from childhood to mature age ; and we believe that, as no mortal can tell the precise moment when the soul is vivified, and as the principle of spiritual life in its commencement is often very feeble, so it is an undoubted truth, that the development of the new life in the soul may be, and often is, very slow ; and not unfrequently that which is called conversion is nothing else but a more sensible and vigorous exercise of a principle which has long existed. This is the theoretical basis for Finney’s “make yourself a new heart”. The “all or nothing transfer of affections from self to God is the moment a “sensible and vigorous exercise of a principle which has long existed”. How different this is from the orthodox understanding of regeneration, which causes a change of character from sinner to saint. Law Works That conviction of sin is a necessary part of experimental religion, all will admit; but there is one question respecting this matter, concerning which there may be much doubt ; and that is, whether a law-work, prior to regeneration, is necessary ; or, whether all true and salutary conviction is not the effect of regeneration. I find that a hundred years ago, this was a matter in dispute between the two parties, into which the Presbyterian church was divided, called the old and new side. The Tennents and Blairs insisted much on the necessity of conviction of sin, by the law, prior to regeneration ; while Thompson and his associates were of opinion, that no such work was necessary, nor should be insisted on. As far as I know, the opinion of the necessity of legal conviction has generally prevailed in all our modern revivals, and it is usually taken for granted, that the convictions experienced are prior to regeneration. But it would be very difficult to prove from Scripture, or from the nature of the case, that such a preparatory work was necessary. Suppose an individual to be, in some certain moment, regenerated ; such a soul would begin to see with new eyes, and his own sins would be among the things first viewed in a new light. He would be convinced, not only of the fact that they were transgressions of the law, but he would also see, that they were intrinsically evil, and deserved the punishment to which they exposed him. It is only such a conviction as this that really prepares a soul to accept of Christ in all his offices; not only as a Saviour from wrath, but from sin. And it can scarcely be believed, that that clear view of the justice of God, in their condemnation, which most persons sensibly experience, is the fruit of a mere legal conviction, on an unregenerate heart. For this view of God's justice is not merely of the fact, that this is his character, but of the divine excellency of his attributes, This is false – law works did not historically involve seeing the excellency of God’s attributes, but only the reality of God’s inevitable judgment of sin. Notice how “saving faith” is coming into view as the important thing and regeneration is moving to the back as a de facto result of the state of mind, admittedly, at this early stage of the doctrine of “sanctification as progressive”, not causing regeneration, but being an evolving result of it. which is accompanied with admiration of it, and a feeling of acquiescence or submission. This view is sometimes so clear, and the equity and propriety of punishing sin are so manifest, and the feeling of acquiescence so strong, that it has laid the foundation for the very absurd opinion, that the true penitent is made willing to be damned for the glory of God. Alexander states Witherspoon’s condemnation of Hopkins view of the ultimate test of disinterested benevolence. Alexander apparently does not know that Hopkin’s “very absurd notion” was NOT a pre-regeneration experience, but rather the ultimate evidence of a changed character by supernatural regeneration. He continues with a discussion of using the means of grace and law works It is very common for the conscience, at first, to be affected with outward acts of transgression, and especially with some one prominent offence. An external reformation is now begun: for this can be effected by mere legal conviction. To this is added an attention to the external duties of religion, such as prayer, reading the Bible, hearing the word, &c. Every thing, however, is done with a legal spirit; that is, with the wish and expectation of making amends for • past offences; and if painful penances, should be prescribed to the sinner, he will readily submit to them if he may, by this means, make some atonement for his sins. But as the light increases, he begins to see that his heart is wicked; and to be convinced that his very prayers are polluted for want ofright motives and affections. He, of course, tries to regulate his thoughts, and to exercise right affections; but here his efforts prove fruitless. It is much easier to reform the life than to bring the corrupt heart into a right, state. The case now begins to appear desperate, and the sinner knows not which way to turn for relief, and, to cap the climax of his distress, he comes at length to be conscious of nothing but unyielding hardness of heart. He fears that the conviction which he seemed to have, is gone, and that he is left to total obduracy. In these circumstances he desires to feel keen compunction, and overwhelming terror, for his impression is, that he is entirely without conviction. The truth, however, is, that his convictions are far greater, than if he experienced that sensible distress which he so much courts. In this case, he would not think his heart so incurably bad, because it could entertain some right feeling, but as it is, he sees it to be destitute of every good emotion, and of all tender relentings. He has got down to the core of iniquity, and finds within his breast a heart unsusceptible of any good thing. Does he hear that others have obtained relief by hearing such a preacher, reading such a book, conversing with some experienced Christian? he resorts to the same means, but entirely without effect. The heart seems to become more insensible, in proportion to the excellence of the means enjoyed. Though he declares he has no sensibility of any kind, yet his anxiety increases; and perhaps he determines to give himself up solely to prayer and reading the Bible ; and if he perish, to perish seeking for mercy. But however strong such resolutions may be, they are found to be in vain; for now, when he attempts to pray, he finds his mouth as it were shut. He cannot pray. He cannot read. He cannot meditate. What can he do? Nothing. He has come to the end of his legal efforts ; and the result has been, the simple, deep conviction that he can do nothing; and if God does not mercifully interpose, he must inevitably perish. During all this process he has some idea of his need of divine help ; but until now, he was not entirely cut off from all dependence on his own strength and exertions. He still hoped that, by some kind of effort or feeling, he could prepare himself for the mercy of God. Now he despairs of this, and not only so, but for a season he despairs, it may be, of salvation - gives himself up for lost. I do not say, that this is a necessary feeling, by any means, but I know that it is very natural, and by no means uncommon, in real experience. But conviction having accomplished all that it is capable of effecting, that is, having emptied the creature of self-dependence and self-righteousness, and brought him to the utmost extremity - even to the borders of despair, it is time for God to work. The proverb says, "Man's extremity is God's opportunity:" so it is in this case; and at this time, it may reasonably be supposed, the work of regeneration is wrought; for a new state of feeling now experienced. Upon calm reflection, God appears to have been just and good in all his dispensations; the blame of its perdition the soul fully takes upon itself; acknowledges its ill-desert, and acquits God. "Against thee, thee only, have sinned and done this evil in thy sight, that thou mightest be justified when thou speakest, and be clear when thou judgest." The sinner resigns himself into the hands of God; and yet is convinced that if he does perish, he will suffer only what his sins deserve. He does not fully discover the glorious plan according to which God can be just and the justifier of the ungodly who believe in Jesus Christ. Law works is the normal experience, but not a necessary experience before regeneration The above is not given as a course of experience which all real Christians can recognize as their own, but as a train of exercises which is very common. And as I do not consider legal conviction as necessary to precede regeneration, but suppose there are cases It has been admitted, however, that legal conviction does in fact take place in most instances, prior to regeneration ; and it is not an unreasonable inquiry, why is the sinner thus awakened? What good purpose does it answer? The reply has been already partially given, but it may be remarked, that God deals with man as an accountable, moral agent, and before he rescues him from the ruin into which he is sunk, he would let him see and feel, in some measure, how wretched his condition is; how helpless he is in himself, and how ineffectual are his most strenuous efforts to deliver him from his sin and misery. He is, therefore, permitted to try his own wisdom and strength. And finally, God designs to lead him to the full acknowledgment of his own guilt, and to justify the righteous Judge who condemns him to everlasting torment. Conviction, then, is no part of a sinner's salvation, but the clear practical knowledge of the fact that he cannot save himself, and is entirely dependent on the saving grace of God. Regarding Edwards’ Religious Affections His work on the Affections is too abstract and tedious for common readers ; but it is an excellent work, although I think his twelve marks might with great advantage be reduced to half the number, on his own plan. The experimental exercises of religion are sure to take their complexion from the theory of doctrine entertained, or which is inculcated at the time… All good conduct must proceed from good principles; but good principles cannot exist without a knowledge of the truth. "Truth is in order to holiness;" and between truth and holiness there is an indissoluble connexion… An argument against telling seekers to use the means of grace In some places, anxious inquirers are told that, if they will hold on praying and using the means, God is bound to save them ; as though a dead, condemned sinner could so pray as to bring God under obligation to him, or could secure the blessings of the covenant of grace, by his selfish, legal striving. These instructions accord very much with the self-righteous spirit which is naturally in us all; and one of two things may be expected to ensue, either that the anxious inquirer will conclude that he has worked out his salvation, and cry peace ; or that he should sink into discouragement and charge God foolishly, because He does not hear his prayers, and grant him his desires. There is another extreme, but not so common among us. An argument against the opposite – telling people not to use the means of grace There is another extreme, but not so common among us. It is, to tell the unconverted, however anxious, not to pray at all - that their prayers are an abomination to God, and can answer no good purpose, until they are able to pray in faith. The writer happened once to be cast into a congregation where this doctrine was inculcated, at the time of a considerable revival, when many sinners were cut to the heart, and were inquiring, what must we do to be saved? He conversed with some who appeared to be under deep and awful convictions, but they were directed to use no means, but to believe, and they appeared to remain in a state of perfect quiescence, doing nothing, but confessing the justice of their condemnation, and appearing to feel that they were entirely at the disposal of Him, who " has mercy on whom he will have mercy." The theory, however, was not consistently carried out, for while these persons were taught not to pray, they were exhorted to hear the gospel, and were frequently conversed with by their pastor. But this extreme is not so dangerous as the former, which encourages sinners to think that they can do something to recommend themselves to God, by their unbelieving prayers. So using the means of grace could be self-reliance, not using the means of grace could be impenitence. What can a seeker do? That will be the subject of the rest of the book. Alexander spends a chapter discussing different temperaments and psychological reasons for depression. He dismisses all manifestations of the Holy Spirit that he does not understand as “enthusiasm”. He considers the Shakers (not Quakers) to be insane. Enthusiasm may have a tendency to insanity; and some people are so ignorant of the nature of true religion as to confound it with enthusiasm. I will go further and declare, that, after much thought on the subject of enthusiasm, I am unable to account for the effects produced by it, in any other way, than by supposing that it is a case of real insanity. Diseases of this class are the more dangerous9 because they are manifestly contagious. The very looks and tones of an enthusiast are felt to be powerful by everyone; and when the nervous system of any one is in a state easily susceptible of emotions from such a cause, the dominion of reason is overthrown, and wild imagination and irregular emotion govern the infatuated person, who readily embraces all the extravagant opinions, and receives all the disturbing impressions which belong to the party infected. Without a supposition such as the foregoing, how can you account for the fact, that an educated man and popular preacher, and a wife, intelligent and judicious above most, having a family of beloved children, should separate from each other; relinquish all the comforts of domestic life, and a pleasant and promising congregation, to connect themselves with a people who are the extreme of all enthusiasts - the Shakers? In a town in New Hampshire, the writer, when in the neighborhood, was told of the case of a young preacher, who visited the Shaker settlement, out of curiosity, to see them dance, in which exercise their principal worship consists: but, while he stood and looked on, he was seized with the same spirit, and began to shake and dance too ; and never returned, but remained in the society. But, there being no demand for his learning or preaching talents, whatever they might be - and he being an able bodied man, they employed him in building stone fences. This species of infatuation, which is called enthusiasm, is apt to degenerate into bitterness and malignity of spirit, towards all who do not embrace it, and then it is termed fanaticism. This species of insanity, as I must be permitted to call it, differs from other kinds in that it is social, or affects large number? In the same way, and binds them together by the link of close fraternity. Alexanders dismissal of the supernatural by the label “enthusiasm” that then can turn into insanity is not far from Sigmund Freud’s classification of the so-called mental aberration he called “conversion syndrome”. Indeed, Alexander comes close to a phrenological explanation. The causes of melancholy and insanity, whether physical or moral, cannot easily be explored. The physician will speak confidently about a lesion of the brain, but when insane persons have been subjected to a post-mortem examination, the brain very seldom exhibits any appearance of derangement. The casuist, on the other hand, thinks only of moral causes, and attributes the disease to such of this class as are known to have existed, or flees to hypothesis, which will account for every thing. There is a remarkable coincidence, however, which has fallen under my observation, between those who assign a moral and those who assign a physical cause for melancholy and madness, in regard to one point. More explanation of spiritual phenomenon as psychological A mob is an artificial body, pervaded by one spirit; by the power of sympathy; for which the French have an appropriate phrase, esprit du corps. If there be any thing in animal magnetism (see Franz Anton Mesmer), which has of late made so much noise, beside sheer imposture, it must be grafted on this principle; for the extent to which human beings may influence each other, by contact or proximity, in certain excitable states of the nervous system, has never been accurately ascertained. In those remarkable bodily affections, called the jerks, which appeared in religious meetings some years ago, the nervous irregularity was commonly produced by the sight of other persons thus affected ; and if, in some instances, without the sight, yet by having the imagination strongly impressed by hearing of such things. It is a fact, as undoubted as it is remarkable, that, as this bcdily affection assumed a great variety of appearances, in different places, nothing was more common, than for a new species of the exercise, as it was called, to be imported from another part of the country, by one or a few individuals. This contagion of nervous excitement is not unparalleled; for whole schools of young ladies have been seized with spasmodic or epileptic fits, in consequence of a single scholar being taken with the disease. There are many authentic facts ascertained in relation to this matter, which I hope some person will collect and give to the public, through the press. It will not be thought strange then, that sympathy should have a powerful influence in increasing and modifying the feelings which are experienced in religious meetings; nor is it desirable that it should be otherwise. Readers may be surprised that a minister is providing a physical reason for what previous generations saw as a spiritual (demonic or the Holy Spirit) phenomenon. This was Scottish common Sense Realism. Alexander attributes most “religious affections” to sympathy, a psychological phenomenon that preachers can exploit with “new measures”. Is it then judicious, by impassioned discourses, addressed to the sympathies of our nature, to raise this class of feelings to a flame? Or to devise measures by which the passions of the young and ignorant may be excited to excess? That measures may be put into operation, which have a mighty influence on a whole assembly, is readily admitted; but are excitements thus produced really useful? They may bring young people, who are diffident, to a decision, and as it were, constrain them to range themselves on the Lord's side, but the question which sticks with me, is, does this really benefit the persons? In my judgment, not at all, but the contrary. If they have the seed of grace, though it may come forth slowly, yet this principle will find its way to the light and air, and the very slowness of its coming forward, may give it opportunity to strike its roots deep in the earth. If I were to place myself on what is called an anxious seat, or should kneel down before a whole congregation to be prayed for, I know that I should be Strangely agitated, but I do not believe that it would be of any permanent utility. But if it should produce some good effect, am I at liberty to resort to any thing in the worship of God which I think will be useful? If such things are lawful and useful, why not add other circumstances to increase the effect? Why not require the penitent, to appear in a white sheet, or to be clothed in sackcloth, with ashes on his head? And these, remember, are Scriptural signs of humiliation. And on these principles, who can reasonably object to holy water, to incense, and the use of pictures or images in the worship of God? All these things come into the church upon this same principle, of devising new measures to do good; and if the anxious seat is so powerful a means of grace, it may soon come to be reckoned among the sacraments of the church. The language of experience is, that it is unsafe and unwise to bring persons, who are under religious impressions, too much into public view. The seed of the word, like the natural seed, does not vegetate well in the sun. Be not too impatient to force into maturity the plant of grace. Water it, cultivate it, but handle it not with a rough hand. The opinion entertained by some good people, that all religion obtained in a revival is suspicious, has no just foundation. At such times, when the Spirit of God is really poured out, the views and exercises of converts are commonly more clear and satisfactory, than at other times, and the process of conversion more speedy. But doubtless, there may be expected a considerable crop of spurious conversions, and these may make the greatest show; for the seed on the stony ground, seems to have vegetated the quickest, of any. And this is the reason that, after all revivals, there is a sad declension in the favorable appearances; because that which has no root must soon wither. In looking back, after a revival season, I have thought, how would matters have been if none had come forward, but such as persevere and bring forth fruit? Perhaps things would have gone on so quietly, that the good work would not have been called a revival. But ministers cannot prevent the impressions which arise merely from sympathy — neither should they attempt it; but, when they are about to gather the wheat into the garner, they should faithfully winnow the heap; not that they can discern the spirits of men, Here is a major difference between the American New Light Calvinists like Nettleton, Beecher and Finney operating with the presumption that the changes caused by regeneration are discernable in the Inquiry Room and ministers educated at Princeton in Scottish Common Sense Realism that did not believe the changes caused by regeneration can be identified in the Inquiry Room. This difference accounts for the shift from BEST to BIST systems in the Inquiry Room after the civil War. The evidence of the shift was clear before the Civil War. Methodist minister Nathan Bangs said in his 1857 biography that new Light Calvinists were promoting faith at the altar as something that needed no evidence of supernatural change. He challenged the idea of “faith in your faith” as absurd. “In the nature of things a fact, and its evidence must precede the belief in it and its evidence, otherwise we make the existence of the fact depend upon our faith, which is simply absurd." Archibald Alexander continues with a warning to ministers that assume their congregations are saved: Scottish Common Sense Realism limited the activity of the Holy Spirit to quickening the word, while the American New Light Calvinists attributed salvations to the moving of the Holy Spirit on the people. so great a change, that, even in the view of the world who observe it, the subject appears to be "a new man." An entire revolution has taken place in his principles of action as well as in his sentiments respecting divine things. Now those who would ascribe all experimental religion to mere natural feelings, artificially excited, must believe that there are no such transformations of character as have been mentioned; and that all who profess such a change are false pretenders. But this ground is manifestly untenable; for no facts are more certain than such reformations; and if there be men of truth and sincerity in the world, they are to be found among those who have undergone this moral transformation. Surely there are no phenomena now taking place in our world half so important and worthy of consideration, as the repentance of an habitual sinner; so that he utterly forsakes his wicked courses, and takes delight in the worship of God and obedience to his will. Let it be remembered, that these are effects observed only where the gospel is preached, and in some instances, numerous examples of such conversions from sin to holiness occur about the same time, and in the same place. Here is the problem. When critics of various forms of New Light Calvinism talk about means and ends, or cause and effect, in regard to metaphysical means of regeneration on one hand as axiomatic, and then talk about “new measures’ (as if these are in a separate category of phenomenon), as detrimental, how do we know where the Holy Spirit ends and flesh or demons begin? And if you really believe in predetermination, couldn't there be a modern minister that burns brighter and demands change quicker by virtue of the Holy Spirit doing a quicker work than in conjunction with a minister with less zeal? Obviously, we must consider the possibility, as Paul Washer reminds us, that "False teachers are God's judgment on people who don't want God, but in the name of religion plan on getting everything their carnal heart desires. That's why ... (a false teacher) is raised up. Those people who sit under him are not victims of him, he is the judgment of God upon them because they want exactly what he wants, and it's not God". But is it not wise to consider that an Elijah will demand obedience to God more vehemently than a member of the Sanhedrin whose place in the community is dear to him? In the Bible, it is ALWAYS those outside the mainstream of religious acceptability that God uses most forcefully. The people of Israel said "Moses who?", and repeated history when they said of the uneducated Apostles, "these that have turned the world upside down are". Scottish Common Sense Realism was apposed to New Measures primarily because it objected to the idea that the Holy Spirit was present to do an immediate experiential work not restricted to moral persuasion of the Word of God. This was the great divide between American New Light Calvinism and Scottish Common Sense Realism. Scottish Common Sense Realism did not pretend to be able to distinguish between Spirit and flesh. It restricted the activity of the Holy Spirit in meetings to quickening the Word of God. Archibald Alexander is about to refer to a "mighty wind" that is a definate, immediate experience that radically and instantly changes an indifferent crowd into an attentive congregation as nothing more than the effect of natural human sympathy. If you read the acounts of George Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards in the First Great Awakening, they saw the "mighty wind" as the movement of the Holy Spirit. (For a succinct history of different perceptions of the activity of the Holy Spirit in the Three Great Awakenings, please read Lyman Atwaters article in the 1876 Princeton Review.) The reader should ask himself, do you agree with Alexander? Were the ministers in the Great Awakenings deluded? Here, from the 1857 Nathan bangs biography, is the prevalent view of the “religious excitements” of the Presbyterian New Light Calvinist (Hopkinsian and Bellamite) Camp Meetings of the Second Great Awakening: WERE THE "RELIGIOUS EXCITEMENTS" OF THE PRESBYTERIAN (HOPKINSIAN AND BELLAMITE) CAMP MEETINGS PRIMARILY THE RESULT OF INDIVIDUAL SYMPATHY OR ORCHESTRATED SYMPHONY? The American Dictionary of the English Language Published by Noah Webster in 1828 has these definitions: SYMPATHY: The quality of being affected by the affection of another… with feelings correspondent in kind, if not in degree…Sympathy is produced through the medium of organic impression. AFFECTION: A bent of mind towards a particular object, holding a middle place between disposition, which is natural, and passion, which is excited by the presence of its exciting object. DISPOSITION: State of being disposed...temper or natural constitution of the mind...Inclination; propensity; the temper or frame of mind...we say, a disposition in plants to grow in a direction upwards DISPOSED: Set in order; arranged; placed; adjusted; applied; bestowed; inclined. In modern language, "the way a thing is, or the reason it acts as it does". INDIVIDUAL: individual man…individual soul…individual labor or exertions. SYMPHONY: A consonance or harmony of sounds. So, are "religious excitements" primarily the result of INDIVIDUAL SYMPATHY OR ORCHESTRATED SYMPHONY? You must decide for yourself. INDIVIDUAL SYMPATHY: If the "religious excitements" were the result of individual sympathy, then it was caused by individuals seeing and hearing something and being affected to the point of irrational behavior, even humiliating debasement in front of friends and family. ORCHESTRATED SYMPHONY: If the "religious excitements" were the result of orchestrated symphony, then it was caused by the movement of the Holy Spirit affecting seekers with immediate experience of truth, and demonic spirits affecting skeptics with feelings of damnation, causing them to behave irrationally, or crazy, which is a good definition of the damned when they experience truth. You are about to read Archibald Alexander's limited view of the Holy Spirit. This is the view taught at Princeton Theological Seminary to George Washington Gale, who taught it Charles Finney, who rebelled against it. Being in a part of the country where I was known, by face, to scarcely anyone, and hearing that there was a great meeting in the neighborhood, and good work in progress, I determined to attend. The sermon had commenced before I arrived, and the house was so crowded that I could not approach near to the pulpit, but sat down in a kind of shed connected with the main building where I could see and hear the preacher. His sermon was really striking and impressive, and in language and method, far above the common run of extempore discourses. George Whitefield would have said Alexander resisted the movement of the Holy Spirit, or he might have said he was stupid, meaning, voluntarily resisting the common grace of the Holy Spirit. I saw few persons through the whole house who escaped the prevailing influence; even careless boys seemed to be arrested and to join in the general outcry. But, what astonished me most of all was, that the old tobacco-planters, whom I have mentioned, and who, I am persuaded had not heard one word of the sermon, were violently agitated. Every muscle of their brawny faces appeared to be in tremulous motion, and the big tears chased one another down their wrinkled cheeks. Here I saw the power of sympathy. George Whitefield would have said the tobacco-planters did not resist the movement of the Holy Spirit. The feeling was real, and propagated from person to person by the mere sounds which were uttered; for many of the audience had not paid any attention to what was said; Alexander HAS to believe it was passed through sounds because from his Scottish Common Sense Realism perspective, it could not have been the Holy Spirit affecting people apart from the Word preached. George Whitefield would say Alexander can not imagine that people can be affected by the immediate experience of the Holy Spirit because his theology prohibits that possibility. I think at this point it would be helpful if readers learned about the prevailing view of psychology as the explanation for the activity of the soul just before the Civil War in the article phrenology. but nearly all partook of the agitation. The feelings expressed were different, as when the foundation of the sacred temple was laid; for while some uttered the cry of poignant anguish, others shouted in the accents of joy and triumph. The speaker's voice was soon silenced, and he sat down and gazed on the scene with a complacent smile. When this tumult had lasted a few minutes, another preacher, as I suppose he was, who sat on the pulpit steps, with his handkerchief spread over his head, began to sing a soothing and yet lively tune, and was quickly joined by some strong female voices near him; and in less than two minutes the storm was hushed, and there was a great calm. It was like pouring oil on the troubled waters. I experienced the most sensible relief to my own feelings from the appropriate music; for I could not hear the words sung. But I could not have supposed that any thing could so quickly allay such a storm; and all seemed to enjoy the tranquility which succeeded. George Whitefield would have said the minister who sang the song was led by the Holy Spirit. The disheveled hair was put in order, and the bonnets, &c. gathered up, and the irregularities of the dress adjusted, and no one seemed conscious of any impropriety. Indeed, there is a peculiar luxury in such excitements, especially when tears are shed copiously, which was the case here. George Whitefield would have said the Holy Spirit had his way in that meeting, not that natural human sympathy made everyone feel a peace.

|